Vs.

RFK STADIUM DEAL FACT CHECK: Cutting Through the Noise

There’s a lot being said about the proposed agreement between the District of Columbia and the Washington Commanders to develop the RFK Campus. Many criticisms of the deal are misleading, lack important context, or just plain wrong. Here are a few examples. Don’t fall for them!

$1.1 billion is the third biggest public subsidy for a football stadium in the country.

the commanders are building and paying for their stadium.

the city’s investment will pay to refurbish the entire 174-acre RFK campus.

But for the record: even if it was, it’s not even close to the largest subsidy for a stadium.

DC’s investment is focused on the infrastructure needed to unlock all 174 acres of the RFK campus: roads, utilities—required for building new housing—and public space that benefit the entire site, whether a stadium is built or not. It’s true that the stadium will be the economic anchor of the project, but it will use only 16 acres (just 9%) of the site and the team—not the District—is paying to design and build it.

Importantly, this infrastructure spending is spread over four years, averaging $125 million annually. That’s just 0.6% of the District’s FY26 budget of $21.8 billion and 4.8% of its capital budget. In other words: a modest, manageable investment that fuels far greater returns.

By contrast, cities like Nashville ($1.26 billion) and Buffalo ($850 million) committed massive taxpayer funds directly to stadium construction. In DC, 75% of the RFK project is privately funded. The District’s share, just 25% of the total cost, supports much more than football: it brings housing, retail, parks and new opportunity to one of the city’s most underused sites.

The major difference?

This time, the team is paying for the stadium, not the taxpayers.

The commanders should pay rent comparable to that of the washington nationals.

Unlike the Nationals deal, where the city paid to build the stadium, the Commanders are footing the bill for their new home, and they’ll own it once it’s built. Think of it like building your own house. If you pay to build it and you own it, you’re not also paying rent.

That means no public financing, no city-backed debt. Just a private investment that delivers public return.

They will, however, pay a nominal lease on the plaza and riverfront sites as part of a phased development strategy. That land currently generates zero revenue for the District. Under the agreement, the developer is required to build out public infrastructure, parks, and affordable housing in the early phases, all at no upfront cost to taxpayers.

The strategy of using a “staged rent deal” is a common feature in public-private development agreements where rents start low and are tied to development milestones and is used to jumpstart early investment, while private development absorbs all the upfront costs. Rents then increase over time as property values grow and public land ownership remains intact all while community benefits and use of the land skyrockets. This strategy was used with City Center, Audi Field and The Yards.

the team will own the stadium it will build, but the District will keep the tax revenue.

all the revenue generated by the stadium goes to the team.

None of the District tax revenue generated by stadium events goes to the team—not ticket sales, not concessions, not merchandise, and not income taxes.

This is spelled out clearly in the publicly released Term Sheet, on page 2, under “Public Benefits and Community Investments”, which states:

"No District tax revenues generated by stadium events, including ticket sales, concessions, merchandise, or income taxes, will be directed to the team."

Instead, that revenue will go back into the District’s budget to fund essential services and community investments. The RFK stadium deal has been intentionally structured to ensure a fair return to taxpayers and protect public resources.

But remember, this project is about much more than a stadium. The stadium only takes up 9% of the campus’s 174 acres. When the full RFK site is developed, it’s projected to generate $5.1 billion in new revenue over 30 years. Just $1.4 billion of that goes to the Stadium Fund. The remaining $3.6 billion flows into the city’s general fund, money that pays for schools, public safety, libraries, and services.

RFK doesn’t take money away from other priorities.

it helps fund future ones.

The proposed investment in RFK will come at the expense of spending on other District priorities.

Here’s the truth: the $1.1 billion investment in RFK is coming from a separate bucket of money — the capital budget — which is only used for big construction projects like roads, buildings, and infrastructure. It’s not the same pot that pays for teachers, firefighters, or social services.

A lot of that money is actually recycled funds, like the Ballpark Fee that used to pay for Nationals Park. That money can’t be used for schools or other daily services. It has to go toward projects like this.

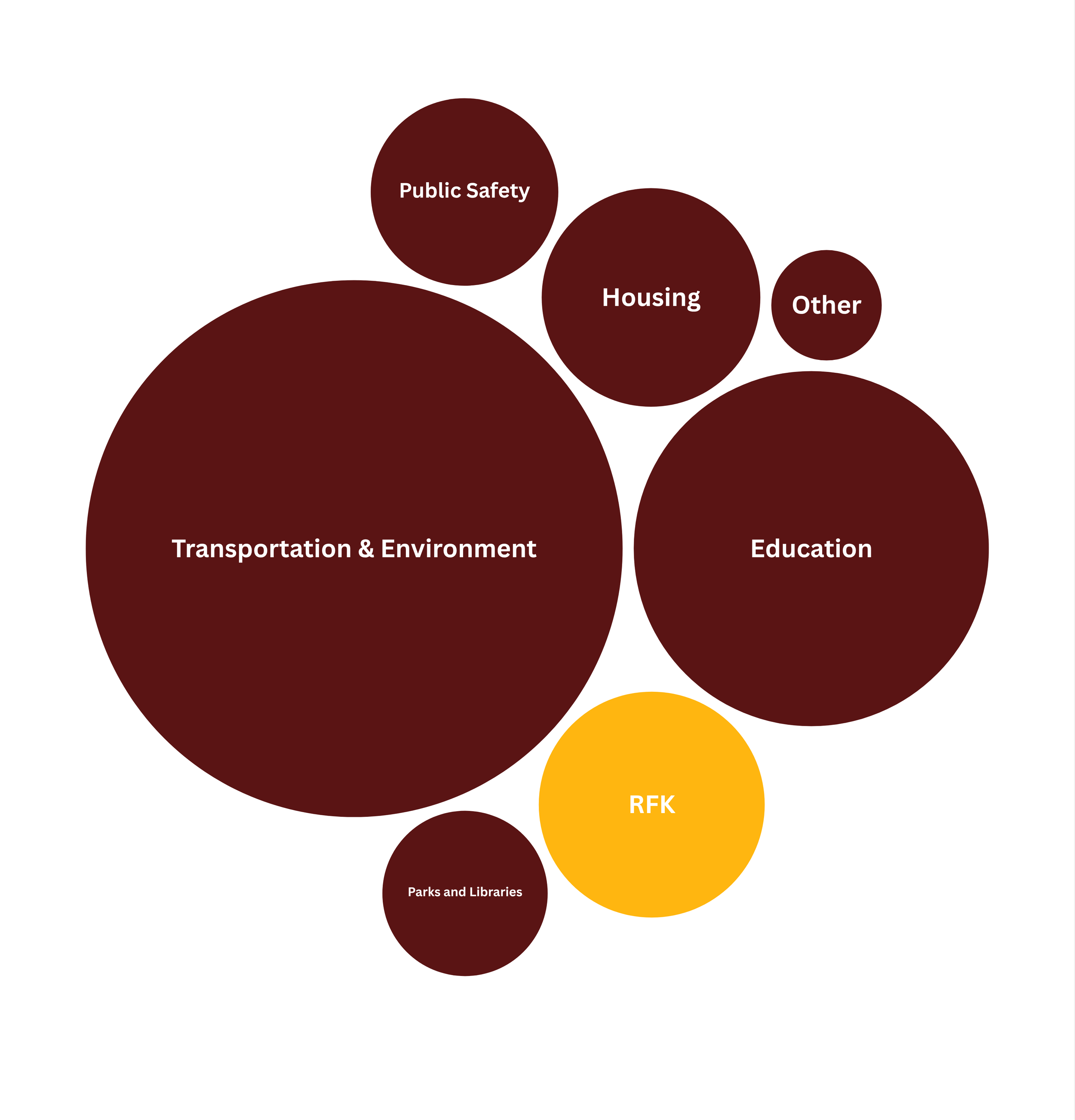

And over 7 years, RFK will use just 5% of the city’s construction budget — with nearly half still going toward transportation and the environment, and more than 20% toward school upgrades.

More importantly, this project pays off over time. It turns a fenced-off, unused site into:

Thousands of new homes, including affordable housing

Jobs for DC residents

New bars, restaurants and retail

And new tax revenue that helps fund city services in the long run

This isn’t just about football, it’s about transforming an asphalt wasteland into a thriving neighborhood. It’s about investing in something that will serve all of DC for decades to come.

how do the RFK costs compare to the rest of the District’s proposed capital budget?

Click to enlarge

The parking spaces in the agreement aren’t just for the stadium. They are for the entire 174-acre destination.

There are too many Proposed parking parking spaces in the rfk agreement.

Some folks are comparing the 8,000 planned garage spaces at RFK to the 1,250 at Nationals Park, but that’s an apples-to-oranges comparison. The RFK plan is much bigger. It’s not just parking for a stadium, it’s parking for the whole 174 acres of parks, shops, housing, and community space. That’s four times the size of The Wharf.

The parking is meant to support the full site, not just game days. Yes, football games draw big crowds, nearly triple what the Nationals averaged last season. But the garages will also serve residents who will ultimate live there, visitors, concert goers, festivals, and families using all the new public spaces.

Most importantly, this is intended to be smart planning to protect the surrounding neighbors. Without enough structured parking, surrounding streets in Ward 6 and Ward 7 could be overwhelmed by traffic and cars, which is exactly what planners want to avoid. Garages help keep that spillover in check, while freeing up streets for people, not just parking.

We don’t have to choose.

The RFK plan delivers both.

The District should invest in housing or other community needs on the rfk campus and not sports stadiums.

This isn’t just about a stadium, it’s about finally putting 174 acres of fenced-off, unused land to work for the people of DC and that includes thousands of new homes.

The agreement sets the stage for up to 6,500 new housing units, with nearly 30% set aside as affordable. That’s more than many full-scale housing developments in the city and it’s made possible by unlocking infrastructure investment through the stadium.

The stadium acts as the catalyst to speed up the construction of roads, utilities, and transit access needed to build out the rest of the site. Without it, that kind of housing development could take decades, or never happen at all.

We’ve seen what happens when there is no catalyst:

At the McMillan Reservoir District, the District gained control of the site in 1987 and it took nearly 40 years to break ground.

Hill East, it took nearly 20 years from the time the land was transferred to the District to see substantial housing built.

The RFK approach is how you accelerate housing, not delay it. And it’s how you make sure the community can see lasting benefits. Not just a stadium, but a real neighborhood where residents can truly live and thrive.

The Commanders pay for 70% of the entire deal. DC taxpayers will see new housing, businesses, and tax revenue necessary to sustain core government services.

this is a bad deal for dc taxpayers

The Commanders pay for more than 70% of the stadium and invest $2.7 billion dollars into the project; the second largest private stadium investment in US history. DC’s spending goes primarily toward infrastructure, which is necessary to build housing, retail and amenities.

The Commanders $2.7 billion dollar investment is also the largest private investment in DC history. This deal is a generational opportunity to build new housing, generate more city revenue, and bring the Commanders home.